Moses Fleetwood Walker: The forgotten first black baseball player

If you were to roam around the average American town and ask the casual sports fan who the first black professional baseball player was, the near unanimous answer would be what you think it would be.

Jackie Robinson.

But Robinson was the first African American to break the color barrier in one of America’s big four professional sports leagues (MLB, NBA, NFL, NHL), not the first African-American to play professional baseball.

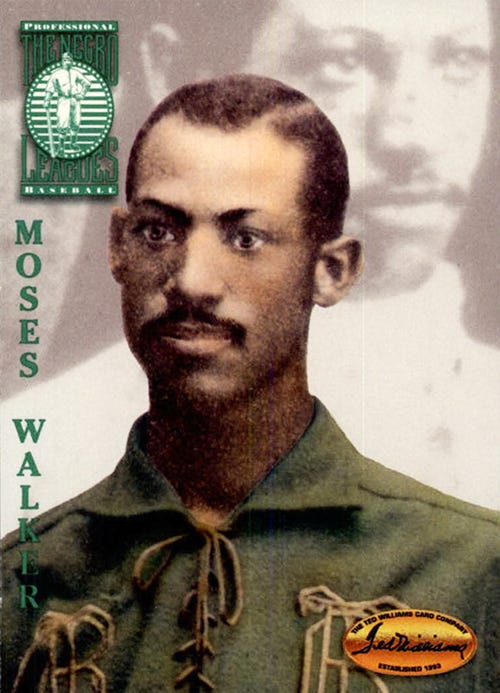

That honor belongs to one Moses Fleetwood Walker, or Fleet Walker as he was known during his playing days.

Walker was born on October 7, 1856 in the eastern Ohio community of Mount Pleasant. The third of six children, it is unclear when Walker started playing baseball, but the first record of him playing organized baseball was when his father — Moses W. Walker — was called to serve the Second Episcopal Methodist Church as its pastor in Oberlin, Ohio.

The Walker family moved to Oberlin in 1877 and Fleet Walker enrolled in Oberlin college the same year. Baseball at Oberlin was initially limited to interclass play and Walker quickly established himself as the starting catcher and leadoff hitter for his graduating class.

During his junior year at Oberlin in 1880, Walker hit a grand slam and caught in a victory over the senior nine. The next year in 1881, Oberlin established its first intercollegiate varsity team, which featured Walker, his brother Weldy (Who would go on to become the second black baseball player to play professionally) and Harlan Burket were all black players who starred on the team.

In the final exhibition of their inaugural season, Oberlin played the University of Michigan, winning 9–2. Sources from the time say players and coaches were so impressed with Walker and teammate Arthur Packer that they invited them to transfer and play ball with them next season as Wolverines.

Before this could happen though, Walker participated in another key game during the summer of 1881 in what would be a precursor to the fervent racism that black baseball players like Walker would experience for the next 60–70 years.

Walker was paid to play semi-professionally during that summer for the White Sewing Machine Company of Cleveland. On August 21, The Whites (ironically named, I know) traveled to Louisville, Kentucky to play a game against the Louisville Eclipse, who would go on to become a charter professional team in the American Association the following year in 1882.

The Eclipse players objected to Walker playing because he was black, and the White Sewing Machine Company Club responded by holding Walker out of their starting lineup. The tension between the two clubs climaxed in the second inning when Walker’s replacement injured his hand and the Whites needed to insert a new catcher. Walker initially took the field and warmed up before the inning started, making impressive throws along the way. But, two Eclipse players left the field in protest, which forced Walker back to the bench and caused the Whites to sub their third baseman in behind the plate before eventually losing to Louisville, 6–3.

Upon returning to Ann Arbor, U of M’s baseball team put together an impressive season in 1882, going 10–3 in part due to Walker’s prowess in hitting for average and power at the plate, while also being an impressive catcher behind it.

His play during the 1882 collegiate season earned him the chance to establish himself as a top prospect at the national level. That chance came later the same summer in a high end amateur league in New Castle, Pennsylvania.

The New Castle Neshannocks, known as the Nocks, performed well with Walker as their catcher and the local press gave Walker glowing reviews for his play.

“(Walker is) one of the best catchers in the country” and “a gentleman in every sense of the word both on the ball field and off,” wrote the New Castle Papers at the time.

A year passed after his time with the Nocks and in 1883, Walker finally received the chance to play professional baseball.

William Voltz, who was the manager of Toledo’s entry into the Northwestern League, signed Walker as a catcher for the city’s first professional baseball team in 1883.

Important to note, catching in the 1880’s was an absolutely brutal job to undertake on a baseball diamond. Back then, catchers didn’t have much in the way of protective equipment outside of a fask mask, on top of there being only think layered leather gloves in most situations to catch with as well.

A Toledo batboy reflected on Walker’s career after it was long over and basically verified that Walker played under very similar circumstances.

“He occasionally wore ordinary lambskin gloves with the fingers slit and slightly padded in the palm; more often he caught barehanded,” said the batboy.

So not only did Walker catch with no chest protector, shin guards, or any kind of catcher’s mitt, Walker was also exposed to the consistent, fervent racism that was commonly levied against black athletes of that time period.

Walker would go on to play in 60 of 84 games in what would be a championship season for the Toledo Entry. He hit a respectable .251, but played remarkably well behind the plate where he earned praise from local media as arguably the best defensive catcher in the league.

However, even with Walker’s exceptional play, the 1883 season in the Northwestern League was what many considered the beginning of segregating black players in baseball across the United States.

Many historians point toward Cap Anson bringing his Chicago White Stockings team to Toledo that season as the tipping point moving toward segregation. Anson was a hall of fame caliber player who was well-known across the country and his skill on the field was only matched by his racial bigotry both on and off of it.

The Toledo Daily Blade captured the back and forth between the Toledo Club and Anson’s Chicago club, all the while painting a picture of Toledo fighting for Walker’s right to play against the racist Anson and the rest of his bigoted teammates.

“Walker, the colored catcher of the Toledo Club, was a source of contention between the home club and the Chicago Club. Shortly after their arrival in the city, the Toledo Club was informed that there was objection in the Chicago Club to Toledo’s playing Walker, the colored catcher,” wrote the Daily Blade.

“Walker has a very sore hand, and it had not been intended to play him in yesterday’s game, and this was stated to the bearer of the announcement for the Chicago[an]s,” continued the Daily Blade. “Not content with this, the visitors declared with the swagger for which they are noted, that they would play ball ‘with no d****d n****r.”

“[T]he order was given, then and there, to play Walker and the beefy bluffer (The paper was referring to Anson and his racial tirades) was informed that he could play or go, just as he d**n pleased,” Noted the Daily Blade. “Anson hauled in his horns somewhat and ‘consented’ to play, remarking, ‘We’ll play this here game, but won’t play never no more with the n****r in.’ ”

Toledo’s manager, Charlie Morton (not to be confused with the modern day Major League Baseball pitcher of the same name), called Anson’s bluff and the game was played, but Anson’s statement before that game on August 10, 1883 set a precedent in baseball for more than the next half century.

While the argument of whether or not to continue to include black baseball players in professional leagues raged on, Toledo’s success in the Northwestern League earned them entry into MLB’s recognized top league in the country at the time in 1884, the American Association.

Toledo and Walker did not replicate their success at the lower level, as they finished 8th out of ten teams in the league and Walker hit a respectable .263 across the 42 games he played in their 104 game regular season.

Walker’s major league debut that year fatefully happened in Louisville, thus having his MLB debut come full circle with his first experience of overt racism in America’s pastime that happened some 3 years earlier.

Walker and his Toledo squad lost and Walker’s poor defensive performance during the game may very well be attributed to the rampant abuse he was subjected to by fans, media, opposing players, and his very own teammates.

No better example of the disadvantages and racism Walker faced came from one of his teammates, pitcher Tommy Mullane, in an article by the New York Age in January of 1919 long after the 1884 American Association season had come and gone.

“Toledo once had a colored man who was declared by many to be the greatest catcher of the time and greater even than his contemporary, Buck Ewing. Tony Mullane, than whom no pitcher ever had more speed,” claimed the Age, “was pitching for Toledo and he did not like to be the battery partner of a Negro.”

“He [Walker] was the best catcher I ever worked with, but I disliked a Negro and whenever I had to pitch to him I used to pitch anything I wanted without looking at his signals, said Mullane.

“One day he signaled me for a curve and I shot a fastball at him. He caught it and came down to me. He said, ‘I’ll catch you without signals, but I won’t catch you if you are going to cross me when I give you signals.’ And all the rest of that season he caught me and caught anything I pitched without knowing what was coming,” recalled Mullane.

Walker, despite hitting 23 points above league average and having the third highest batting average on the team at the time, was released by Toledo on September 22, 1884, effectively ending his professional baseball career at the MLB level of the time.

Walker afterward would go on to play high-end organized baseball for the next five years and became the last black man to play in an organized professional baseball game on August 23, 1889 in the International League until Jackie Robinson played for Montreal in the same league in 1946.

Walker struggled with alcoholism and often carried a gun with him to games he played in, for fear of what could happen if too many overtly racist fans were in attendance.

In 1891, he stabbed a white man to death after a racially-charged, drunken argument in Syracuse, New York. Remarkably at the time, Walker was found not guilty by a jury of 12 white men, but it was still another tumultuous incident in what was a roller coaster life for Walker.

After his playing career Walker would go on to work as a railway clerk, hotel and opera house manager, co-editor of a black-owned newspaper, and a novelist among other professional ventures.

Walker died on May 11, 1924 of Pneumonia and was buried in an unmarked grave until 1991 in Union Cemetery in his hometown of Steubenville, Ohio.